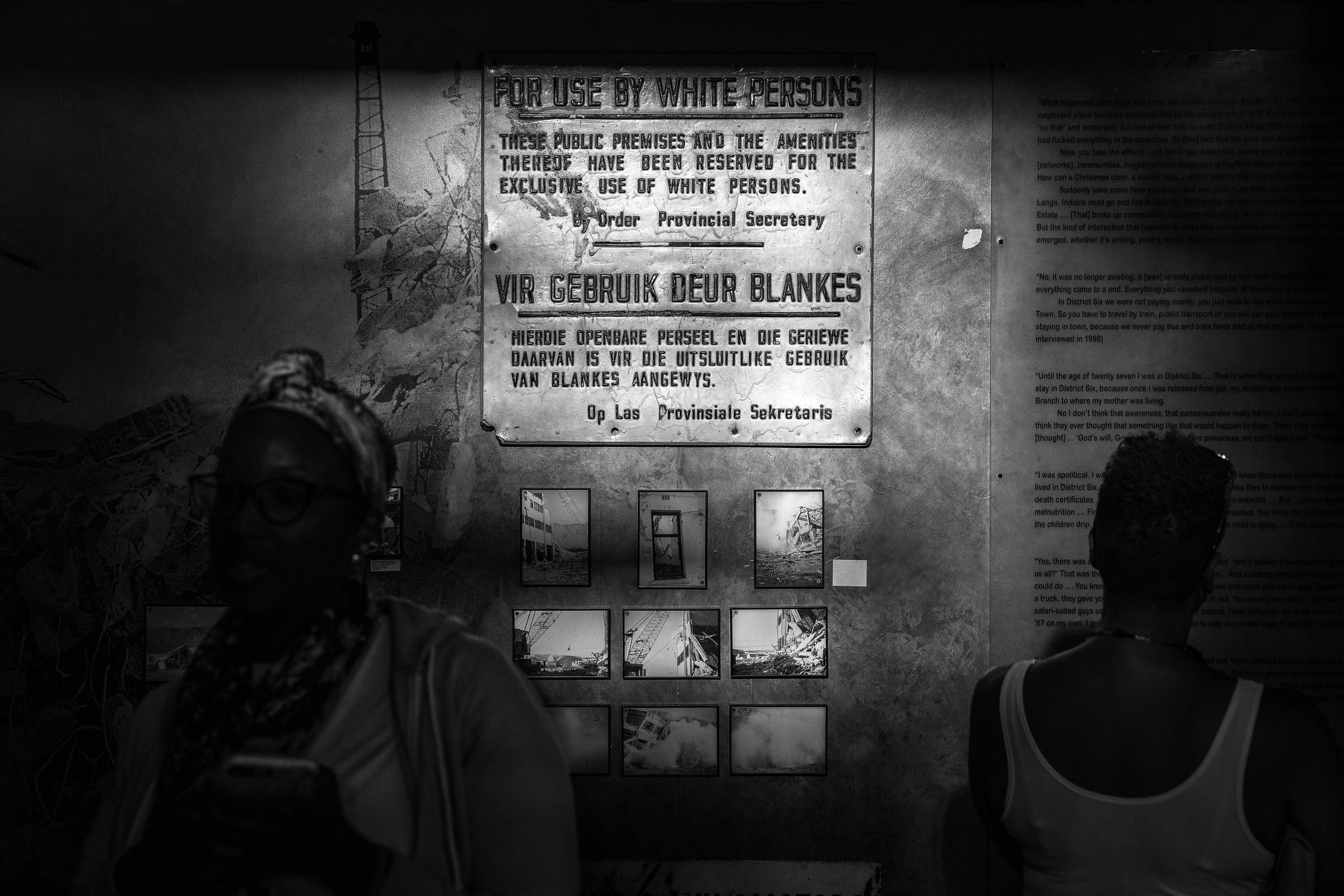

In February 1966 the South African apartheid regime decided to make a central and densely inhabited area of Cape Town at the foot of Table Mountain exclusive to whites.

Over the 15 following years, over 60,000 blacks and a minority of coloureds were forced out of the so-called District Six, which had ample infrastructure and transport links, and sent to barren sandy fields over 30 km from the town center.

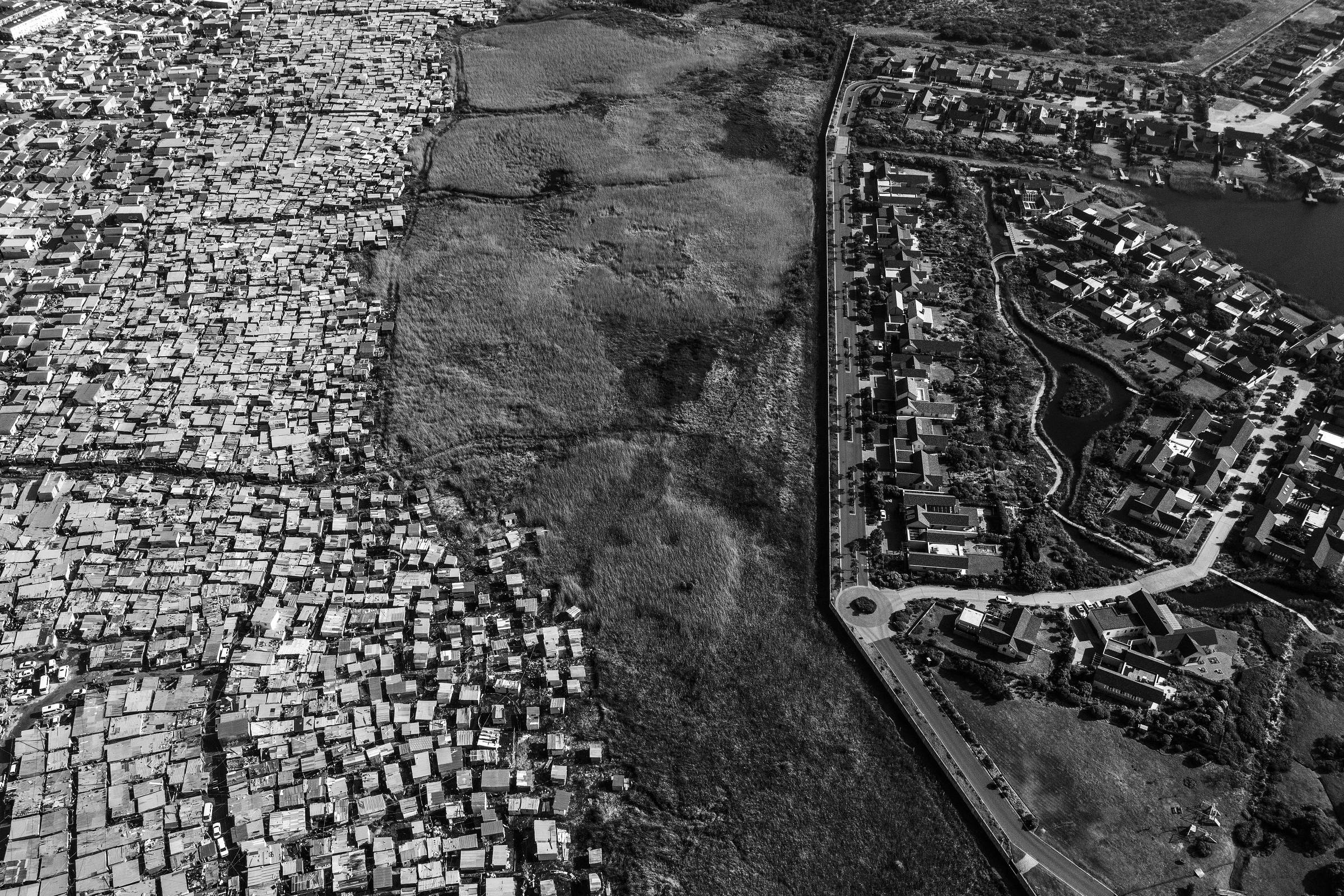

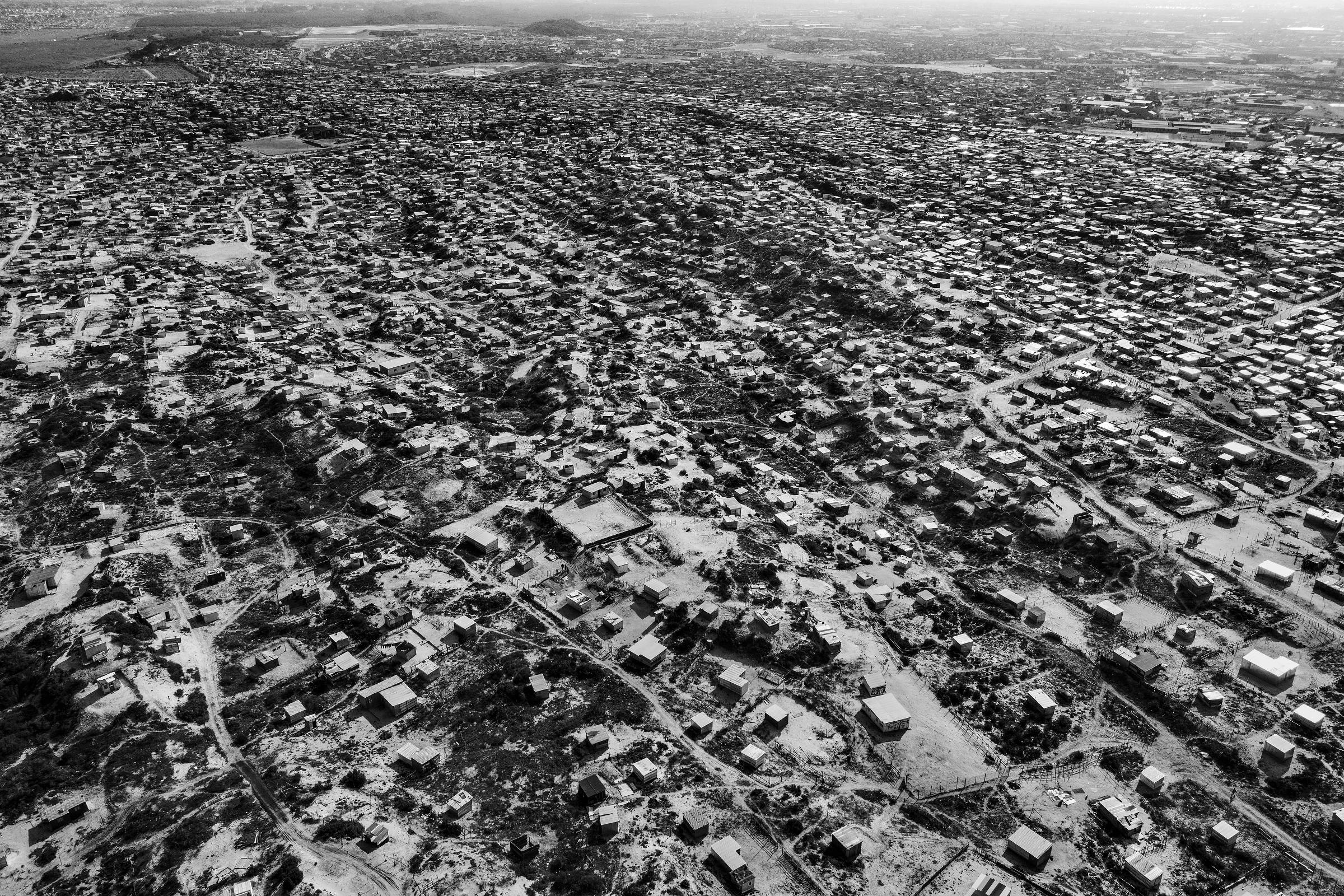

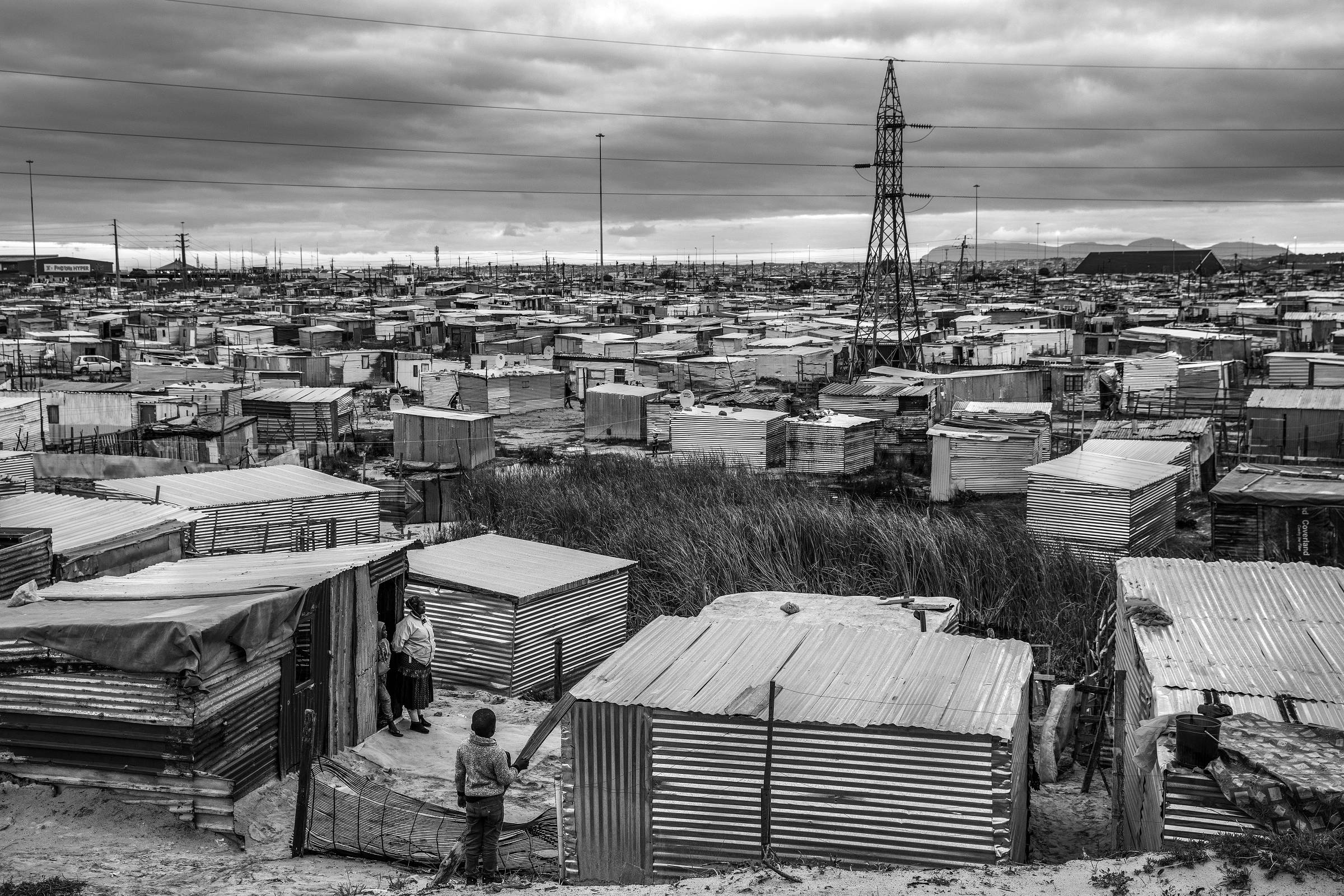

Known as "flats", these areas of Cape Town now include some of the largest and most poverty-stricken shantytowns in South Africa, seen as the country with the highest level of inequality in the world.

Even after the end of the apartheid regime, which was in place from 1948 to 1994, the historic inequality between rich and poor continued growing in South Africa. Today the 10 per cent richest in the country dominate almost 70 per cent of the country's wealth.

Statue of Nelson Mandela at Cape Town"s City Hall. 1960s plaque indicates location exclusive to whites in South Africa. Luxury beach home in Cape Town

In Cape Town, Khayelitsha the name means Our New Home in the Bantu language is the largest of these settlements, known nationally as townships. Of various types, the settlements are usually made of shacks built of sheet metal over wooden frames fixed to the ground.

These so-called "tin cities" are found in almost all the great South African cities, i.e. Johannesburg and its famous township of Soweto. They have ended up reinforcing the geographical segregation between blacks and whites that was already present before apartheid.

In 1913, when South Africa was still a part of the British Empire, the so-called Natives Land Act reserved over 90 per cent of its territory for white landowners. It was a way found to consolidate the power of the English in the country, targets of a longstanding dispute over land, gold and diamonds with the Dutch, the first Europeans to colonise South Africa from 1652.

Over the 25 years since apartheid came to an end, the state has returned around 20 per cent of arable lands to blacks, but the townships are still growing.

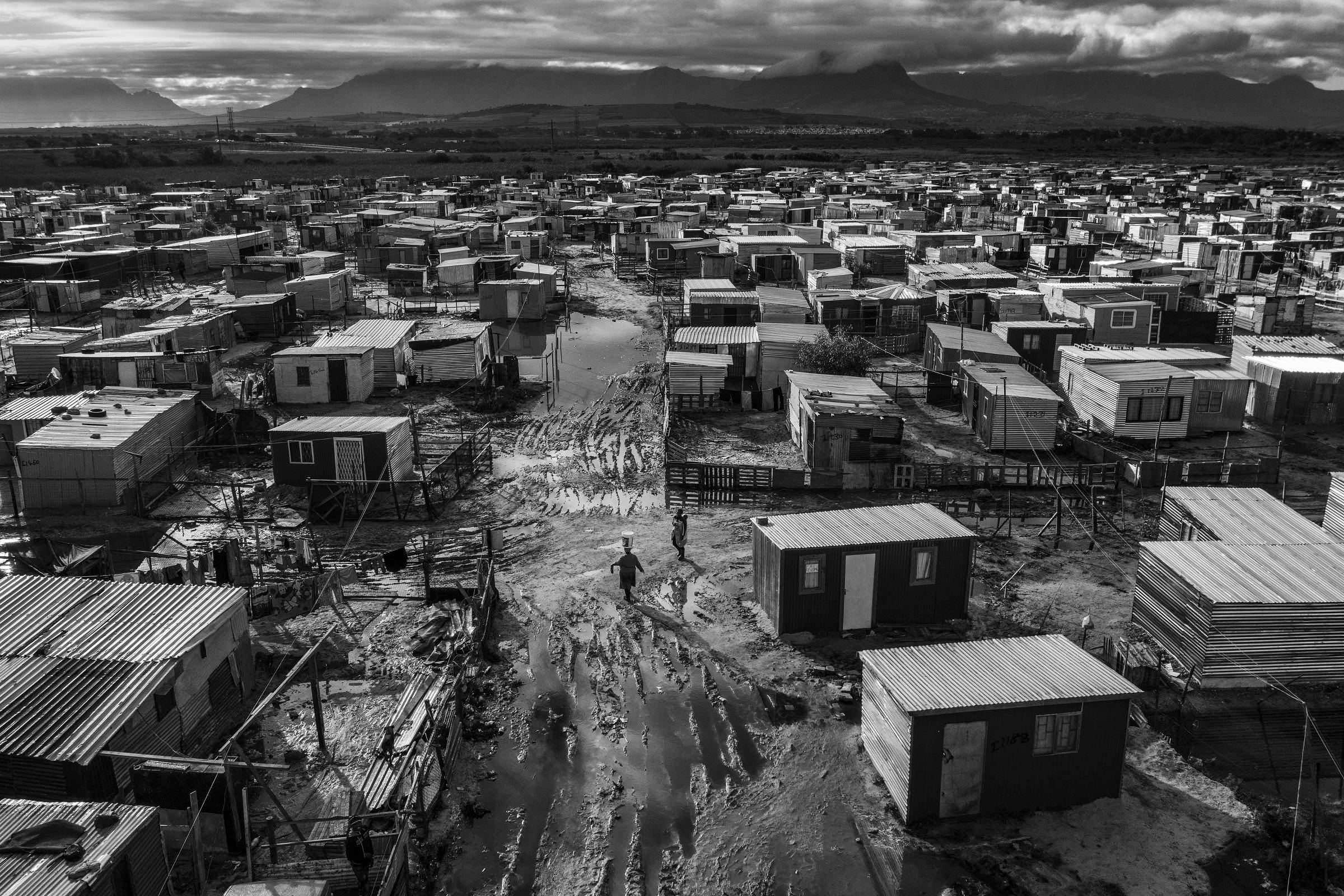

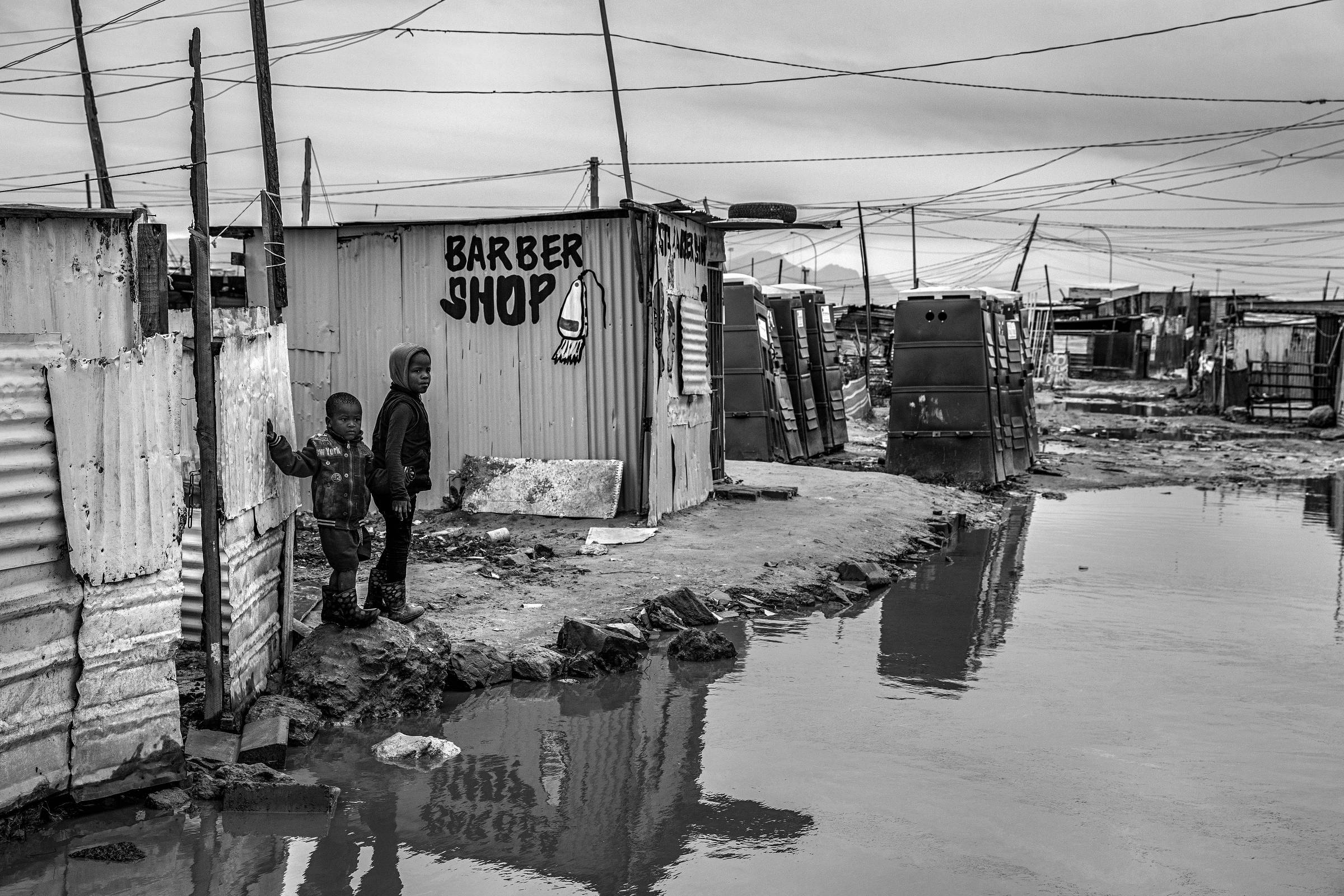

Because of this disordered growth, many of Khayelitsha's 600,000 inhabitants living in the township's most distant edges have no indoor toilets, running water or electricity. Its dirt roads are unpaved, constantly flooded in winter and covered in trash.

Nokuthula Bulana, 32, lives in Khayelitsha and is jobless. She says that simply going out with her children to one of the few and filthy public toilets can be dangerous after dark. Beside the toilets are public taps and broken sinks for doing laundry.

Bulana shares her home with two children and four adults, all unemployed. Despite having finished technical training in financial services, she and the others are unable to find steady work. Thus, the seven family members have to live on less than 4,300 rands (around US$ 290) a month, earned from odd jobs and an invalid uncle's pension.

"We send out e-mails and CVs, but to no avail. My husband has a driver's licence, but even so he can't find a job," Bulana says.

Nokuthula Bulana, 32, resident of Khayelitsha. All four adults in her family are unemployed

South Africa has 57 million inhabitants and one of the world's highest levels of unemployment almost 28 per cent, concentrated mostly among the blacks, who make up 80 per cent of the population. Among them the unemployment rate is higher, reaching 31 per cent and 50 per cent of young people.

In the case of whites, who make up less than 10 per cent of the population, unemployment hovers around 7.5 per cent, well below the level of other minorities such as mixed race and Asians.

"Inequality in South Africa is caused by the job market, but can't be understood separately from its historical roots," says Patrizio Piraino, economist at the University of Cape Town.

"Until apartheid came to an end, society was starkly divided. A person's skin colour dictated the opportunities they would have in life," he says.

During apartheid, not only was the great black majority forcibly pushed out to areas distant from the urban centers which concentrated the best jobs, but they also began going to the worst schools.

Anti-apartheid activist Zukuthin Kleinbaas, 65, recalls being arrested six times in 1976 and whipped on the buttocks after setting fire to a school in the Cape Town township to protest the bad quality schooling provided.

Today, 25 years after apartheid ended, Kleinbaas says that nothing has changed from his perspective. He is unemployed and lives off the earnings of his wife, who works for a German couple.

Over the last three decades, with the increasing use of machinery in farms and mining, two major activities in South Africa, and the ever greater need for skilled workers in industry, unemployment has become a structural problem among the black population.

Since a large portion of South Africans have a very low income, the inequality in relation to those who have jobs, especially whites, is tremendous.

While half of South Africans survive on less than US$ 5 a day, the 10 per cent most wealthy earn on average the equivalent of US$ 290 daily practically the same as French in the same segment.

Children in township over 30 km from the center of Cape Town. Young people play on skates in high income neighbourhood full of shops and restaurants

The income gap between black and white South Africans fell after apartheid came to an end. Nevertheless, inequality rose due to increased disparity among the black majority.

According to the Global Inequality Report produced by the Paris School of Economics, changes introduced to the labor market post-apartheid have contributed to this outcome.

One of the major changes has been a greater offer of better paid employment in the public sector to members of the educated black South African elite.

Since the end of apartheid South Africa has been governed by black presidents, from Nelson Mandela (1994-1999) to the recently elected Cyril Ramaphosa, all belonging to the ANC (African National Congress).

Throughout these years the black elite has been able to thrive, provide their children with better education and open several kinds of businesses that sprung up after the end of the international boycotts against the segregationist regime that were in place until 1993.

As well, and despite a few compensatory measures adopted, land distribution in South Africa remained concentrated post-apartheid. Roughly 70,000 white farmers occupy most of the fertile land in the country.

Farms in South Africa and black labourers at work during harvest time

The global commodities boom of the 2000s enabled this white farming elite to multiply their earnings, preventing further reduction of the inequality between whites and blacks.

From 2009, South Africa underwent a new wave of income concentration under the government of president Jacob Zuma, who resigned last year, charged with almost 700 counts of corruption that favoured friends and family members in deals with state-owned enterprises.

Those who benefited most during this period were the elite of the elite, the 1 per cent wealthiest in the country, who now control over 20 per cent of national income.

Meanwhile, for black South Africans living in poverty, the place of their birth and where they live still dictate their future income level.

And one thing that doesn't help is that since apartheid came to an end the number of townships in South Africa has risen from 300 to almost 2,700.

Erefaan Pearce, 42, believes that it is because he left one such township Mitchell's Plain, in Cape Town that he is now able to earn around 40,000 rands (US$ 2,700) a month.

Specialized in solving computer problems for rich white clients, Pearce left Mitchell's Plain as a teen thanks to the efforts of his mother, terrified of continuing there after her son was stabbed three times in an attempted robbery.

"It's by pure luck that I am where I am today. It would be very hard to repeat this same path if I attempted to do it again," he says.

Thanks to contacts he made with wealthy people at a time when he worked as a DJ and from his present work, Pearce earns enough to be able to rent a home in a middle-class neighbourhood in Cape Town for 11,000 rands (US$ 742) monthly.

But he can't see his way to saving up enough to put down on a property close to the town center, where one-bedroom flats go for around 1,4 million rands (approximately US$ 95,000).

Property prices are much higher in other areas of Cape Town, such as Hout Bay and Llandudno beaches or in Constantia, where very few homes are without a swimming-pool and prices often exceed 15,000,000 rands (about US$ 1,000,000).

Luxury homes close to the beach and boats in a marina in Cape Town, South Africa

To the contrary of the townships, these are areas teeming with services and infrastructure and kept under the watchful eye of videocameras and private security details. South Africa has around 9,000 private security firms, far more than the 2,700 similar ones registered in Brazil.

Most black people who move around these areas can be seen either early in the morning or in the evening, arriving in vans or waiting for the same kind of rides, widely used in Cape Town, to take them back to the townships.

A return trip from Khayelitsha to downtown Cape Town costs 40 rands (US$ 2.7) in one of these vans and may take almost two hours for each part of the trip.

In a country where almost half the population lives off less than 70 rands (US$4.7) a day, the cost of the commute makes looking for work more difficult and devours a large part of the income of service sector employees, who are paid roughly 140 (US$9.5) a day.

Nonceba Ndlebe, 39, lives in Khayelitsha and says she couldn't afford to leave the township daily to work, as it would add more transport costs to the 167 rands (US$ 11) per week she already spends on school transport for her 11-year-old son.

Nonceba Ndlebe, 39, says leaving the township daily for work is unfeasible

This fact, plus the arrival of another baby, led her to give up the temporary jobs she used to find in hotels in the town center and devote herself instead to a small clothing business and social outreach work in Khayelitsha.

As is the case with other low-income mothers in South Africa, Ndlebe has the right to 420 rands (US$ 28) a month from a federal benefit program for underprivileged children.

The program, which could be described as a type of South African "Bolsa Família", is known as Sassa (for the South African Social Security Agency). It reaches 12 million children and is provided until they are 18.

Homes made of sheet metal in Khayelitsha, Cape Town. In the winter, the streets are flooded and dirty most of the time

According to economist Vimal Ranchhod, from the University of Cape Town, the South African government has had some success with reducing extreme poverty with the aid of programs such as this one and expanding universal access to education.

Based on one of the official standards for measuring poverty namely, a monthly income below US$ 55, the number of South Africans living in extreme poverty fell from 51 per cent in 2006 to 36 per cent in 2011. But it has risen again over the last few years, to around 40 per cent.

Meanwhile, the struggle to overcome inequality faces much greater hurdles, due above all to the dearth of opportunities in the labour market and the unequal distribution of land.

Ranchhod believes that adults who experienced the end of apartheid are still willing to be patient with the slow pace of change in South Africa.

"But the younger generations are much more assertive," he says. "Deprived of hope, they represent a major political and social risk".

"Either this will find chaotic expression or society will have to collectively question what must be done. Unfortunately, collective solutions have never had a great place in our history, only the use of force."

In this sense, South African political groups such as the Economic Freedom Fighters, who have 11 per cent of the seats in the National Assembly, are pressuring the government in favour of an aggressive policy of expropriation of lands in the hands of whites, without payment of compensation.

Even without a positive answer from the government, this idea has sparked reactions from the business community.

There are fears of a crisis similar to what took place in neighbouring Zimbabwe at the end of the 1990s, when lands were confiscated from white farmers in a process that unleashed much violence and led to the collapse of the banking system.

Translated from the Portuguese by Clara Allain

Homeless man collects tins and other recyclable waste in downtown Cape Town