Before the early 1990s, the chimneys of more than a thousand factories dominated northwestern England's landscape. Most of the factories were weaving mills at the height of the industrial revolution in the 19th century.

During this period the first steam engines multiplied the goods and fortunes for an entire generation. First in England; then in the rest of Europe, the US and other parts of the world. In its heyday, Oldham in Greater Manchester was one of the most dynamic places on Earth, connected to the rest of the world by railroads that reached the port of Liverpool.

Today the city of 100 thousand inhabitants looks like a museum. Few chimneys are left, and there is an air of decay -hundreds of small dark-brick houses that housed the workers of the past dot the city.

Above, the ruins of a Hartford weaving factory building that opened in 1907 in Oldham, North West England; below, an abandoned insurance company Building in the center of Oldham.

On Union Street, one of the main streets, the busiest spot appears to be an unemployment center. That's where Brian Melling, 65, started looking for work four years ago.

A former truck driver, his economic life declined along with the Oldham industries, which underwent globalization. Companies found lower wages in Asia, and young and educated people moved to the big cities.

Back in the day, Melling could, as he says, "have a motorcycle, smoke, drink and do whatever he wanted. And even save money. "Today, he lives in a privately subsidized apartment and lives on 73 pounds (US$ 91) a week from unemployment insurance. To save money, he eats low-quality canned food, cold snacks, fruit, and lots of tea.

Melling and the people in his region were mostly responsible for approving brexit in 2016. In a tight victory, 51.9% of those who voted in the referendum chose to leave the European Union and regain the option of closing the UK to immigration and imported products.

In Oldham, support for brexit reached 61%, a rate repeated throughout Greater Manchester. In Greater London, more dynamic and cosmopolitan, the opposite happened: 60% voted to remain in the European Union.

Brian Melling, an unemployed truck driver, subsides on 73 pounds per week from unemployment insurance and lives in a subsidized apartment in Oldham, England

"I voted for brexit because we were better before the common market. We are very poor, and everyone has treated us very poorly," Melling said.

In his opinion, radicalism in Europe has been feeding on a sentiment similar to his. "Look at the yellow jackets in France. People want change. "

For David Soskice, coordinator of the International Inequalities Institute in London, while residents of large cities have done better because they are more educated and globalized, those in the countryside have lost income and status.

That would explain both brexit and Donald Trump in the US, where impoverished midwestern states secured the Republican's victory.

However, the main driver of radicalism and populism, especially in the West, would be the impoverishment of the middle class. This is the result of a mix of globalization, technological advances, the concentration of high-quality education at the top, and financialization of capital over physical production, which has traditionally generated jobs.

It is the middle class, which feels more distance from the rich above, who are turning to Eurocentric, anti-immigration and far-right political parties for solutions.

"They are people who are worried they will fall into the pit of poverty, or that this may happen to their children. They voted for it," Soskice said.

This personal financial decay led Mark Hodgkinson, 58, to march for 14 days and 450 km in defense of brexit, from the interior of England to the Parliament in London.

A resident of Rochdale, in the north of Manchester, the online product salesman saw his two children and friends flee to larger cities like London in search of opportunities that no longer exist where they lived.

"Twenty years ago, there was a lot of work here. Today, young people have no chance," he said.

Economist Branko Milanovic, the author of "Global Inequality" (Harvard University Press), said that what exists today is a "protest vote" against the lack of coherent programs to staunch the shrinking middle class. According to him, the phenomenon has become structural and may soon eliminate the "main driver" of economic growth.

"In an extreme example, there would be demand for a Maserati car on the one hand, and the immense demand for rice and bread on the other. This does not mean that there will be no growth, but it will be of a different kind."

For Martin Wolf, a chief commentator for the British Financial Times, answers like brexit, Trump and other radical ideas "will do nothing to solve the problem." "In fact, it will only make things worse by encouraging people to blame some other group, often more vulnerable," Wolf said, referring to immigration.

Among all regions of the world, however, it is in Western Europe that income inequality still grows more slowly, although it has jumped significantly since the 1980s -mainly because of the increasing accumulation at the top.

In the United Kingdom, the wealthiest 1% has doubled its share of national income since the 80s, and today makes up 12% of the total, according to the Global Inequality Report by economist Thomas Piketty and his team at the Paris School of Economics.

Below the top, however, the income of 500 thousand Britons have fallen in the last five years, and today they live on less than 60% of the national average monthly income.

They are now 4 million workers (1 in 8) with a monthly income of less than 1,100 pounds (US$ 1,370), which classifies them as poor, according to the Joseph Rowntree Foundation based on the criteria of the European Union. This impoverishment coincided with cuts of more than 30 billion pounds (US$ 37 billion) in social benefits in the UK since 2010.

This has helped to double, for example, the demand for the Food Banks among the British since 2013.

"In 2018, we helped nearly 8,000 people. Seven years ago, when we started, there were a hundred," said Lisa Leunig, 52, head of the Oldham Food Bank.

Across the UK, 1.4 million of these gift baskets were distributed only last year -almost twice as many as five years ago.

When Folha visited the Oldham Food Bank, Katherine Storor, 33, was there with her son. A former employee of a weaving shop that closed, she is now in a store earning 250 pounds (US$ 312) per week, and she resorts to the food bank in emergencies.

Katherine says she lives with her mother because she can not rent a house in the city for less than 600 pounds (US$ 750) a month.

A woman begs on the Canary Wharf bridge, an area dominated by multinational banks and companies in London (above); in various points in the English capital and Paris, in France, homeless people live in tents

Across the Channel, France has a similar story.

In the last ten years, about 630,000 people have moved in poverty, many coming from the middle class. Five million people, or 8% of the population, are now considered poor, according to the Inequality Observatory.

The agency considers those living on less than half the French average salary to be poor, or about 855 euros (US$ 960) -the equivalent of renting a 20-square-meter apartment in Paris.

Using the same UK rule (less than 60% of average income), the poor in France would jump to 8.8 million, or 14% of the population.

In the last decade, the number of people served by food programs has nearly doubled to 4.8 million.

Although France still has poverty levels equivalent to half the European average, its increase broke a historical downward trend.

According to the Global Inequality Report, after the "glorious 30 years" (1950-1983) that raised the average income of 99% of France's population by 200% (and the 1% richest by 109%), there was a reversal.

From then on, while the accumulated income growth of the poorest half was 31%, in the wealthiest decile, it increased by 49% -and reached 98% in the top 1%.

With rising wages and capital gains, the wealthiest 10% now earn an average of 109,000 euros per year (US$ 122,000). In the poorest half, the average earnings are 15,000 euros per year (US$ 17,000).

The "yellow vests" protests in France are partly seen as a product of inequality and stemmed, on the one hand, from tax cuts for the richest adopted by president Emmanuel Macron.

They also stemmed from an increase in fuel taxation at the end of 2018, when the demonstrations broke out.

"When people saw their bills rise and others benefited, there was a great deal of discontent," said Lucas Chancel, coordinator of the Global Inequality Report.

The lower taxation on the rich in France, he believes, will only increase inequality.

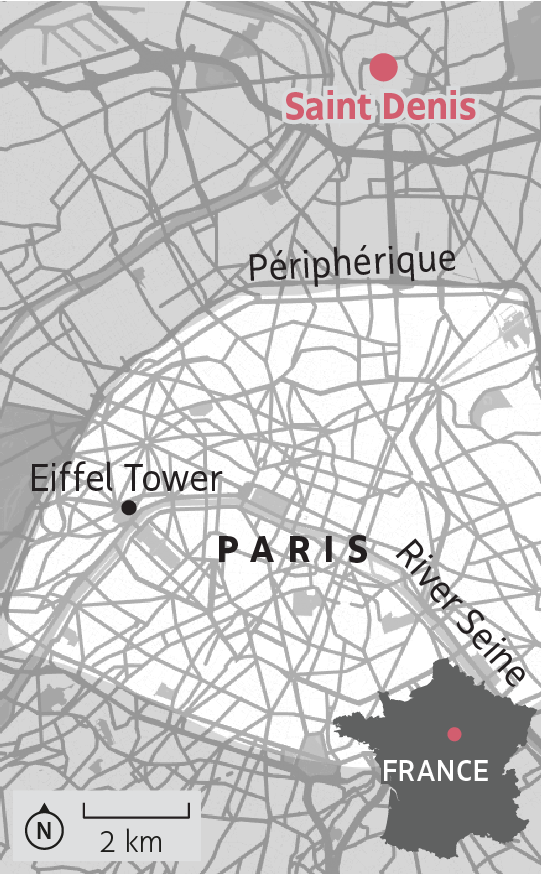

A resident of Saint-Denis, a suburb in the north of Paris and one of France's most impoverished areas, designer Valery Voyér, 45, said she joined the "yellow vests" to protest against the inequalities and precariousness of work in her country.

"Many are there because the situation is tragic, unsustainable. Others, out of solidarity with others," she said.

Valery Voyér (right) said she joined the "yellow vests" to protest inequality in France

Valery says she is forced to work at least 50 hours a week (the official work week in France is 35 hours) to "maintain a certain level."

In response to the demonstrations that have lasted more than six months, Macron announced tax cuts for 15 million families, the aid of up to 1,000 euros (US$ 1,120) for low-income people and the suspension of hospital and school closures until 2022.

In total, the costs of these measures will be 17 billion euros (US$ 19 billion). Macron also advocated stricter immigration policies in a nod to the growing number of sympathizers of the French right.

A couple begs in front of a luxury goods store on Champs Élysées Avenue in Paris

In this scenario of radicalism, Spain surprised the world in April when the Socialists won the parliamentary elections, although without conquering the majority alone.

In this scenario of radicalism, Spain surprised the world in April when the Socialists won the parliamentary elections, although without conquering the majority alone.

In the same elections, Spain voted into Congress Vox, its first right-wing party since 1979.

"There is this revival of the right," said Joan Babiloni, 62, a cinematographer and resident of El Raval neighborhood in Barcelona.

Since the global crisis of 2008-2009, inequality in Spain has risen, and the wealthiest 10% now stands at more than 30% of gross income, compared to 26% of the poorest half.

"The Spanish middle class has always been workers or small business owners with a future. This is over. Now, there is only fear among us, the precarious ones," Babiloni said.

In Paris, Lucas Neves collaborated

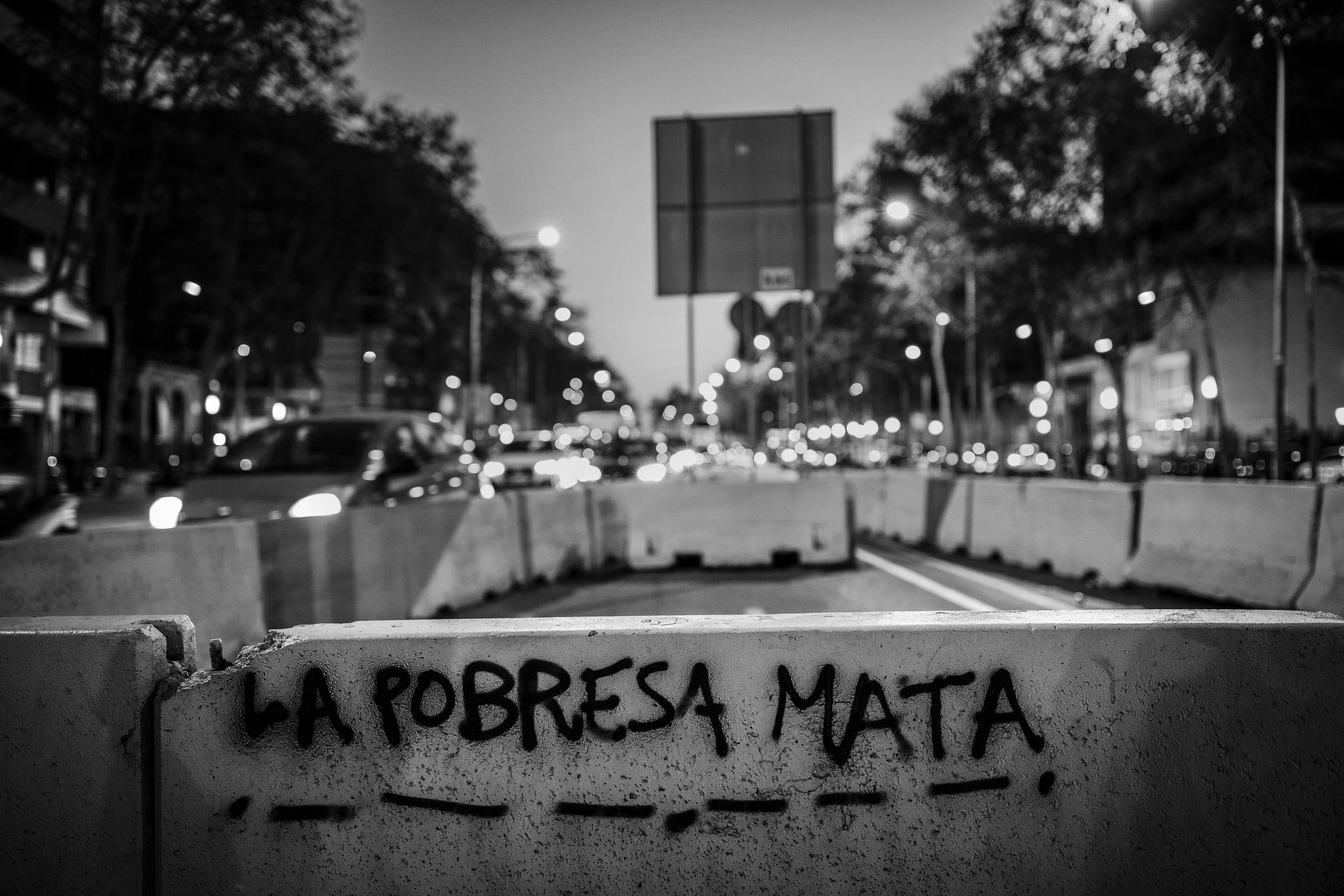

Graffiti in the center of Barcelona, Spain, criticizes income inequality