The discussion of AI (artificial intelligence) ethics is older than the technology itself –at least in fiction.

In 1942, the author Isaac Asimov wrote the "three laws of robotics" in a short story that integrates the book "I, Robot" (1950). The rules provided for the protection of human beings.

Despite having exploded recently and appearing to be something new, the concept of AI outside of fiction emerged at the same time as Asimov's writings.

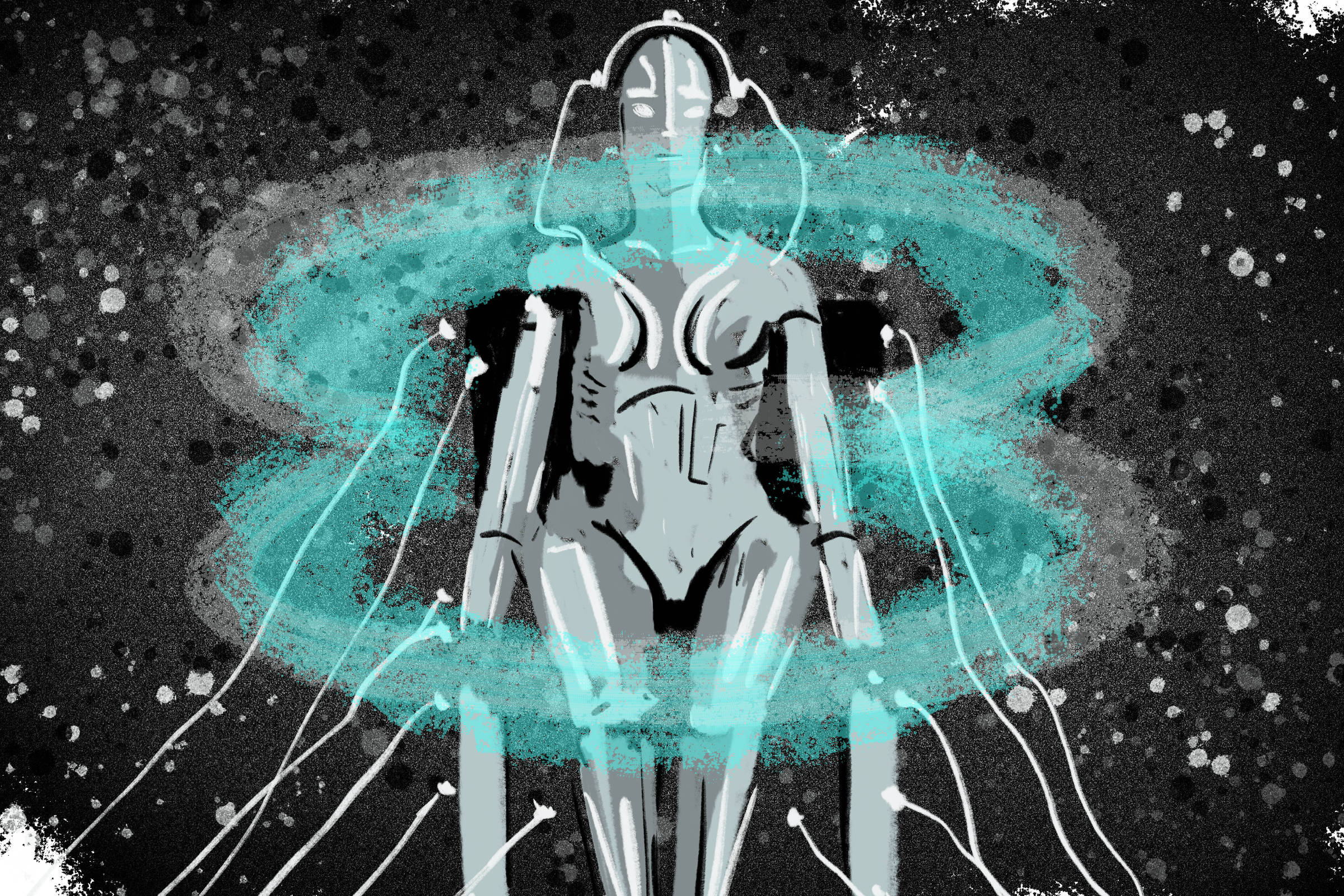

| Carolina Daffara | ||

|

||

The three laws of robotics

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm;

- A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law;

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.

Source: "I, Robot" (Isaac Asimov, 1950)

-

Formally, the term "artificial intelligence" first appeared in 1955. On that occasion, John McCarthy, Marvin Minsky, Nathaniel Rochester, and Claude Shannon proposed a two-month study at Dartmouth College in the USA. They wanted to make machines use language, form concepts and abstractions, solve problems, and be able to improve themselves.

The idea of AI, still without that name, emerged a few years earlier. In 1950, the English mathematician Alan Turing published the article Computing Machinery and Intelligence".

In the text, he discussed the possibility of interaction between machines. He proposed the Turing Test (called the Imitation Game by the author), which assesses the ability of a device to imitate the thinking of a human being.

Turing pointed out that if a machine could imitate a human in its capacities of consciousness - understanding language, learning from conversation, remembering what was said, communicating back, and having common sense - it would mean that the computer would be conscious.

The game consists of asking questions of a person and a computer, without knowing which is which. From the answers, the interrogator tries to identify the human and the machine.

This model received a lot of criticism, and people accused it of failing to assess creative ability and presenting a limited conception of human intelligence.

Turing's expectation was that computers would surpass humans before 2000. However, no computer won the game, which remains one of the goals for AI researchers.

What makes the Imitation Game so difficult is that the interviewer knows that one of the challengers is a machine and the other is a real person. So they will try to spot the computer. Other, simpler, versions of the game have been beat. In these, the interviewer is not aware that they are talking to a machine.

One of the most famous milestones in the history of this technology came in 1997 when IBM's Deep Blue computer defeated then-world champion chess player Garry Kasparov.

In 2016, another milestone: AlphaGo (from Google) won the world championship of the Japanese game Go, considered more complex than chess.

The victories have certainly drawn attention to technology, but they do not demonstrate significant advances in AI.

The approaches used so that computers could play chess were created in 1950 by the American mathematician Claude Shannon. What has changed in these 47 years has been the power of computers and their ability to process information.

Shannon proposed two ways for a computer to play chess. The first uses what experts call brute force. Several (thousands or millions) of possibilities are simulated with each move, and the machine chooses the one it believes to be the best, without thinking about a broader strategy.

The other was to analyze as few moves as possible, thinking of a strategy. In the 50s and 60s, this model, although more complicated, was more common due to the limitations of the computers at the time, so fewer moves were tested.

In the victory over Kasparov, the IBM system used the first approach. Deep Blue evaluated about 200 million positions per second.

"When the dust [of Kasparov's victory] settled, researchers were left with the realization that building an artificial chess champion had not actually taught them much," wrote François Chollet, Google's artificial intelligence researcher, in a scientific article published in November.

"They had learned how to build a chess-playing AI, and neither this knowledge nor the AI they had built could generalize to anything other than similar board games," added Chollet.

In the case of Go, Chollet says he has not yet found an application for the technology used in the victory.

WINTERS IN AI AND MACHINE LEARNING

The ideas that looked good but had no practical application contributed to a massive drop in expectations around AI.

Development of AI has lagged twice in history in periods called "winters." This is a reference to a nuclear winter –a hypothetical phenomenon of global climate cooling after a nuclear war.

Governments that had financed research in AI, like the American and British governments, became disappointed in the results and began cutting funding in AI's early years.

During this winter, researchers adopted other names for the technology to try to get funding. Terms like "machine learning" or "advanced computing" began to appear.

In the 1970s, intelligence once again gained some prestige with the concept of expert systems. They were computer programs focused on imitating a human expert on a specific subject to carry out an activity. So some programs specialized in the analysis of chemical structures and diagnosis of diseases, among others.

They raised expectations, and some of them got off the ground. But there was a lot of work to develop these programs. Also, it was not possible to understand how a machine thought and drew its conclusions-it functioned like a black box.

"People were so disillusioned that they turned away from the field," says Kanta Dihal, a researcher at the University of Cambridge.

Translated by Kiratiana Freelon