The mansion of Mukesh Ambani, India's richest man, is one of the most expensive residences in the world. Named Antilia, it is valued at $ 2 billion second only to Buckingham Palace, where the Queen of England lives.

A single-family of five occupies the 27 floors of Antilia. Six floors are parking lots to house the Ambani car collection. There is a cinema for 50 people, a clubhouse with an exercise room and a basketball court.

From the sidewalk where his "office" is set up, tea salesman Radeshyam Sahu, 45, can see Antilia's last floors. Each morning, Sahu comes out of his kitchenette, where he shares a bathroom with four other families, and goes to the upscale neighborhood of Cumbala Hill to sell six-rupee teacups (US$ 0.10) to bystanders.

Sahu only studied until the first grade, earns 7,000 rupees (US$ 100) a month and has little hope of making progress.

Antilia Building (left) in Mumbai, India; a single family of five occupies the 27 floors of the building, which has six floors for parking, a movie theatre and nine elevators - Ashwin Nagpal/Getty Images

In India, stories of social and economic rise like Prime Minister Narendra Modi, who started his life selling tea like Sahu and came to the rank of leader of the country, are increasingly unlikely.

The likelihood of an Indian born to poor parents rising in life is decreasing, especially for those with low education. Only 8% of Indians whose parents were in the 50% lower education rate were able to reach 25% higher, while in most countries this rate is 12%, according to a World Bank survey.

Factors such as religion and caste also contribute to India having one of the lowest rates of social mobility in the world.

Since the liberalization of the economy in the 1990s, however, India has lifted 170 million people out of poverty. However, inequality has risen.

According to the Global Inequality Report, while the income of the wealthiest 10% in the country increased by 394% between 1980 and 2014, that of the poorest 50% rose 89%. This is less than half of the average income growth in all strata in the period 190%.

Until the 1980s, India was known as the License Raj. Economic policy was statist, with protection of local industries, restrictions on foreign investment, and centralized planning. In the 1970s and 1980s, when the economy was still heavily under government intervention, GDP growth was low - known as the Hindu rate, but no more than 3.5 percent, but inequality was also low.

With the liberalization and bureaucracy of the 1980s and 1990s, the economy gained efficiency because of competition and pro-market reforms.

However, India has moved from a License Raj to a Billionaire Raj. In the 1990s, there were only two Indians on Forbes's list of billionaires.

Today there are 106 Indian billionaires on the Forbes list among them Mukesh Amabani, owner of Reliance Industries and Antilia Mansion.

In recent years, the country's growth has accelerated and surpassed 8% at various times. In 2015, inequality in India reached its highest level since 1922.

Part of this concentration of income is due to the development model adopted by India. India, unlike China, failed to develop a large manufacturing sector after liberalization. The industry is a significant employer, which could absorb much of the millions of unemployed or underemployed people. However, Indian growth has been driven by the information technology sector, which does not generate enough jobs for large portions of the unskilled population.

These people are still stuck in agriculture, which is experiencing a price crisis and growing steadily below GDP. That should not change anytime soon 66% of the Indian population still lives in the countryside.

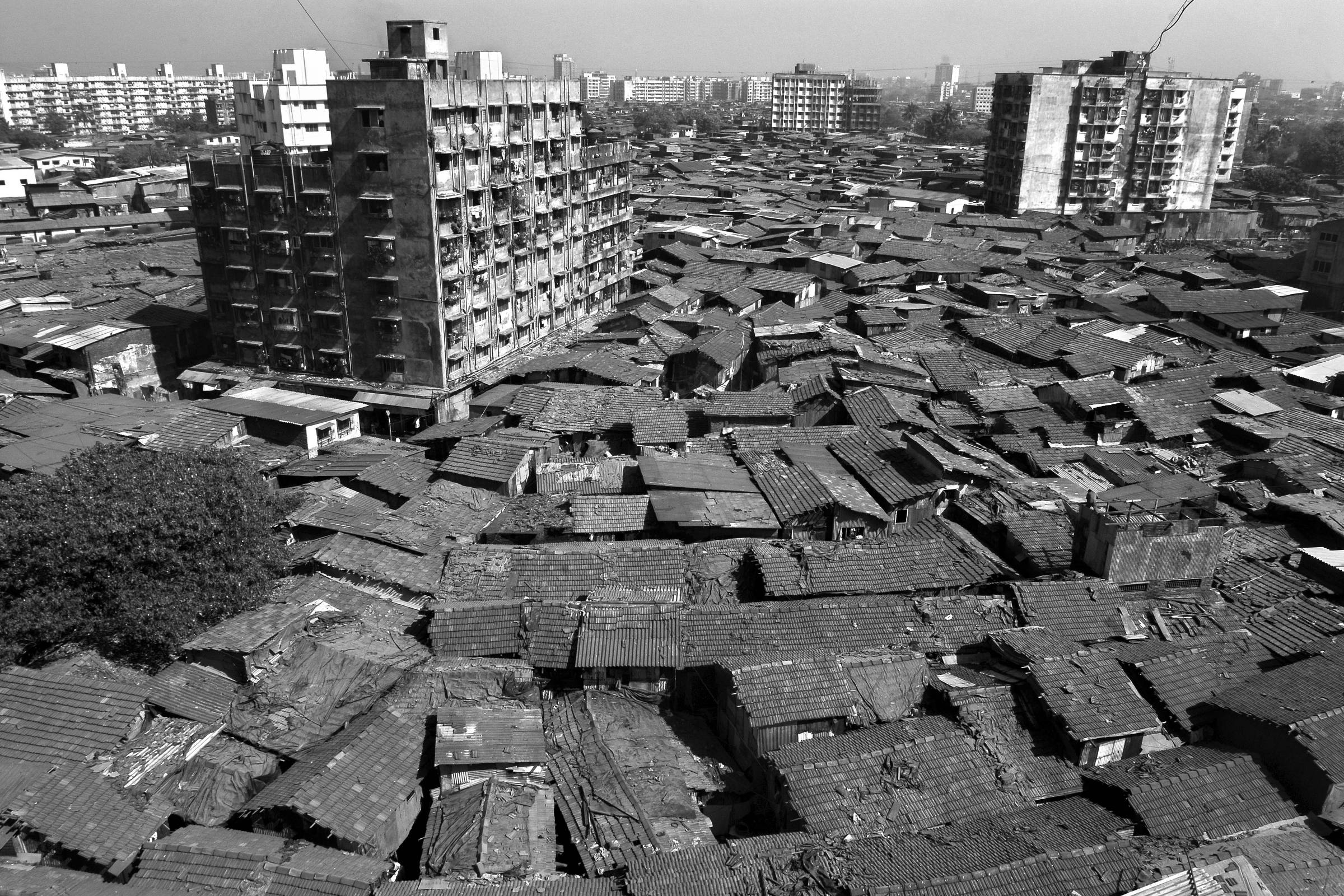

Much of the unskilled rural population that migrates to job-strapped cities ends up living in slums like Dharavi, India's largest.

Panoramic view of a favela in Mumbai, India, and Indians doing their daily activities in the community - Moment Open/Getty Images and Puint Paranjpe/AFP

Asha Jayawant Bagul, 65, came from a village in Maharashtra, Mumbai, about 30 years ago, and settled in Dharavi.

With 1 million inhabitants, it is the third-largest slum in the world behind only Neza in Mexico and Orangi Town in Karachi, Pakistan. It gained fame as the setting for the movie Who Wants to Be a Millionaire.

The vast majority of Dharavi residents must use the smelly public restrooms scattered throughout the favela. There is no basic sanitation. The sewage runs outdoors.

Asha lost her husband four years ago, and her two young children had already died. Today she shares a room in Dharavi with her daughter, Shashikala, 30, and grandson, Mangesh, 9.

Shashikala is a seamstress and earns 7,000 rupees (US$ 100) a month. Asha worked as a cleaning lady but had to stop because she has a hip problem and needs surgery. It cannot be operated on even in the public hospital, where patients need to pay for surgical supplies and medications. "It's too much to spend for the little money we have, we always go to bed hungry," says Shashikala.

Asha Jayawant Bagul shares a room in a favela with her daughter, Shashikala - Javed Atique/Folhapress

Asha's big wish is to eat an apple. The box costs 200 rupees (US$ 2.90). "I haven't eaten fruit for so long; I even forgot the names. I haven't eaten an apple in years," Asha said. She and her daughter have never gone to the movies or eaten at a restaurant. Family fun is watching soap operas and cartoons on the little tube TV.

Arvind Panagariya, who was vice-chairman of the Modi government's planning committee and remains very close to the prime minister, believes that income inequality itself is not a problem. "There is no country in the world that grows more than 7% a year for a decade without increasing some indicators of inequality," said Panagariya, a professor of economics at Columbia University.

From 2004 to 2014, India recorded its highest growth ever, averaging 8% per year. "In my view, for a developing country, fighting poverty is much more important than being obsessed with inequality. If growth is helping to reduce poverty, which is certainly true in India, even if inequality increases, it is still better than not having poverty reduction and having a more equitable distribution. In the 1950s, we were all poor, so there was a fairly equal (poverty) distribution," Panagariya said.

Montek Singh Ahluwalia, who was vice-chairman of the planning committee in the previous government of the Congress party, has the opposite view.

"It is wrong to say that inequality does not matter. Inequality can foster a sense of injustice; when it does, increasing inequality is a problem even if poverty is reduced," said Ahluwalia, the former director of the IMF's independent evaluation office.

The country has not generated enough jobs for the nearly 10 million young people entering the job market every year.

The unemployment rate is 6.1%, the highest since 1972. Compared to the unemployment rate of over 12% in Brazil, it may not seem so high. But unemployment was only 2.2% in 2012.

Today, it is particularly high among 15-29-year-olds. In urban areas, 18.7% of men in this age group and 27.2% of women are looking for a job. In rural areas, 18.7% of men and 13.6% of women.

In this country of 1.3 billion people, formal jobs are hotly contested. In January, for example, 7,000 people - mostly college graduates - applied for 13 waiter positions at a public dining hall in Maharashtra. An Indian Railways competition to hire 63,000 janitors, porters, porters attracted 19 million applicants late last year.

Some envision the possibility of a better life, only for it to regress all over again. Kaikasha Sheikh, 26, took the whole family out of the favela by landing a flight attendant job at Jet Airways.

After two years, she began to put on weight because of hypothyroidism, and the company fired her on the grounds that she could no longer fly because of her health problem. Kaikasha is trying to get another airline job, but it is difficult. She has already applied for vacancies, but she hasn't received anything. Now she works at random events.

Her dad hasn't worked in years. The 19-year-old sister is taking a beautician course, and the 17-year-old brother studies animation. Kaikasha pays the rent, the sister's course, the electricity bill, and the food. She is in debt.

"It will be very difficult to go back to Andheri (slum in northern Mumbai), I saw how life could be better outside the slum," he says.

Her mother paid for her daughter's studies at a bilingual school (Hindi and English) working as a day laborer. "When I got a job, I told her, Mom, I owe you everything, you worked hard so I could study, so now you can stop and rest."

She made between 45,000 and 60,000 rupees a month, depending on how much she flew (between US$ 650 and US$ 850). She wanted to do international flights, but because she lived in the favela, her passport application was rejected twice.

She managed to move her family to the lower-middle-class apartment where they live today and finally received her passport. But she was fired before realizing her dream of traveling abroad.

"We already have significant inequality because of the caste regime," said Rayaprol Nagaraj, professor of economics at the Indira Gandhi Development Research Institute, which is linked to the country's central bank.

"Liberalization has brought growth, but only the most skilled workers have benefited. We put all the eggs in one basket, thinking we would be a software powerhouse, but we need to employ millions of people."