When they were young, farmers Li Hu Hu, 58, and Hao Sanhuan, 54, were forced by their parents to marry without even meeting each other. Li and Hao live in Hohhot, a city in the north close to the border with Mongolia.

"From that time on, it's not worth remembering. It was very hard. Our parents had lots of kids, and they could not take care of them all, "says Hao beside her husband.

With clothes and hands covered with the grime of earth, the couple shows off the small house where they live among chickens and sheep.

Both work on a mushroom farm. With their money from work, they are renovating their house and paying for their children's studies.

At age 28, the youngest graduated in applied chemistry completed a master's and now works in Beijing.

In a country with nearly 1.3 billion people, Li and Hao are among the nearly 800 million Chinese who have left extreme poverty behind since 1978.

Hao Sanhuan and Li Hu Hu work on a mushroom farm financed by the Chinese government in Hohhot; the couple in their house, where they raise sheep and chickens

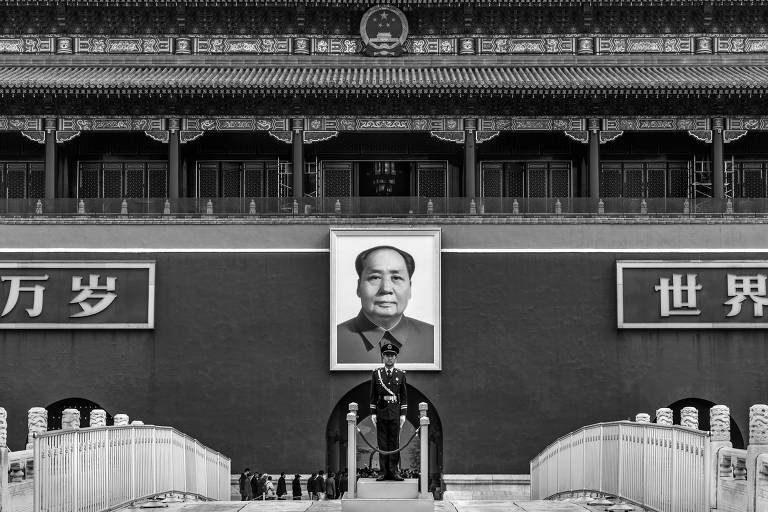

It was two years after the death of Mao Tsé-Tung (1893-1976) responsible for making China a communist country that Deng Xiaoping (1904-1997), then Secretary-General of the Chinese Communist Party, introduced a series of economic reforms that would lead the country to grow about 10 percent a year for a long period until it became the second-largest economy in the world.

Rapid export-led industrialization, low wages (which almost no longer exist) and high productivity helped to transform China.

Now, the goal of incumbent President Xi Jinping, 65, is to eliminate China's misery by 2020.

After Xi took office in 2013, the government considered 89 million people poor in the country. In six years, according to official figures, this total has already been reduced to 13.1 million.

The Chinese state has launched projects focused on rural areas, where incomes are a quarter of what is paid in cities.

Su Gouxia of the China Against Poverty Office says that this year's state budget to fight poverty reaches 3.4 percent of the public budget, or 120 billion yuan (US$ 18.2 billion), more than double that of Bolsa Familia, which serves 13.7 million families).

A Chinese government worker presents statistics about poverty reduction in the country

"We also injected a lot of money into transportation, education and medical services in rural areas," Su said.

The mushroom farm where Li and Hao work in Hohhot is part of this massive effort to subsidize businesses and companies that hire people in miserable situations.

The government invested 650 million yuan (US$ 101 million) into the mushroom farm for an annual production of 5,000 tons of mushrooms, of ten different types.

There is no profit yet, said Wang Hailin, director of the business that employs about 500 farmers. But on average, each person earns between 3,000 and 4,000 yuan per month (US$ 470 to US$ 625), depending on productivity.

This is the around same income that cattle salesman and producer Liu Yongsheng, 43, earns at the Cheng Feng fair in Tongliao, further east and close to the border with North Korea.

With the help of government loans, the managers of the fair lent 100,000 yuan (US$ 60,000) to Liu so he could begin to create and market cattle. Like Liu, another 41 people have received loans since 2016.

"The changes here are huge, and we are much better than when we were young," said Liu, whose dream is to make his 17-year-old son a college student.

The Cheng Feng trade fair trades about 8,000 cattle per auction. A former Chinese military man and member of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) created it.

After setting up the operation, he created a political party cell within the business, an increasingly common configuration in China that Folha found in several of the companies visited.

It is estimated that Chinese Communist Party cells operate in more than 70% of private (including foreign) companies in China, a trend that has been steadily increasing since Xi Jinping's arrival in power. These political hubs serve both to better monitor central government policies and to get rid of local bureaucracies and obtain benefits such as subsidized loans.

In November last year, the official People's Daily reported that Jack Ma, founder of the Alibaba group and one of the wealthiest people in the world, joined the party, following a path already taken by prominent businessmen in the country.

In all, the CCP has nearly 90 million affiliates in China and offers a mobile app so its members can follow Xi Jinping's party guidelines and speeches online.

"In our case, the CCP cell attracted the participation of neighboring merchants to the fair," said Zhang Min, sales manager of Cheng Feng and founder's sister.

According to Yu Xiaohua, a professor at Renmin University in Beijing, another trend in the private sector is the expansion of investment in the countryside. In essence, this investment employs more people in still impoverished areas to escape rising costs and wages in the wealthy regions of eastern China.

At the same time, another government goal for 2020 is to increase the number of Chinese in urban areas to 60%. For this, rural areas became "franchises" of larger cities with 3 million to 5 million residents, allowing people to use their "hukou"a type of internal passport to travel freely between the two areas.

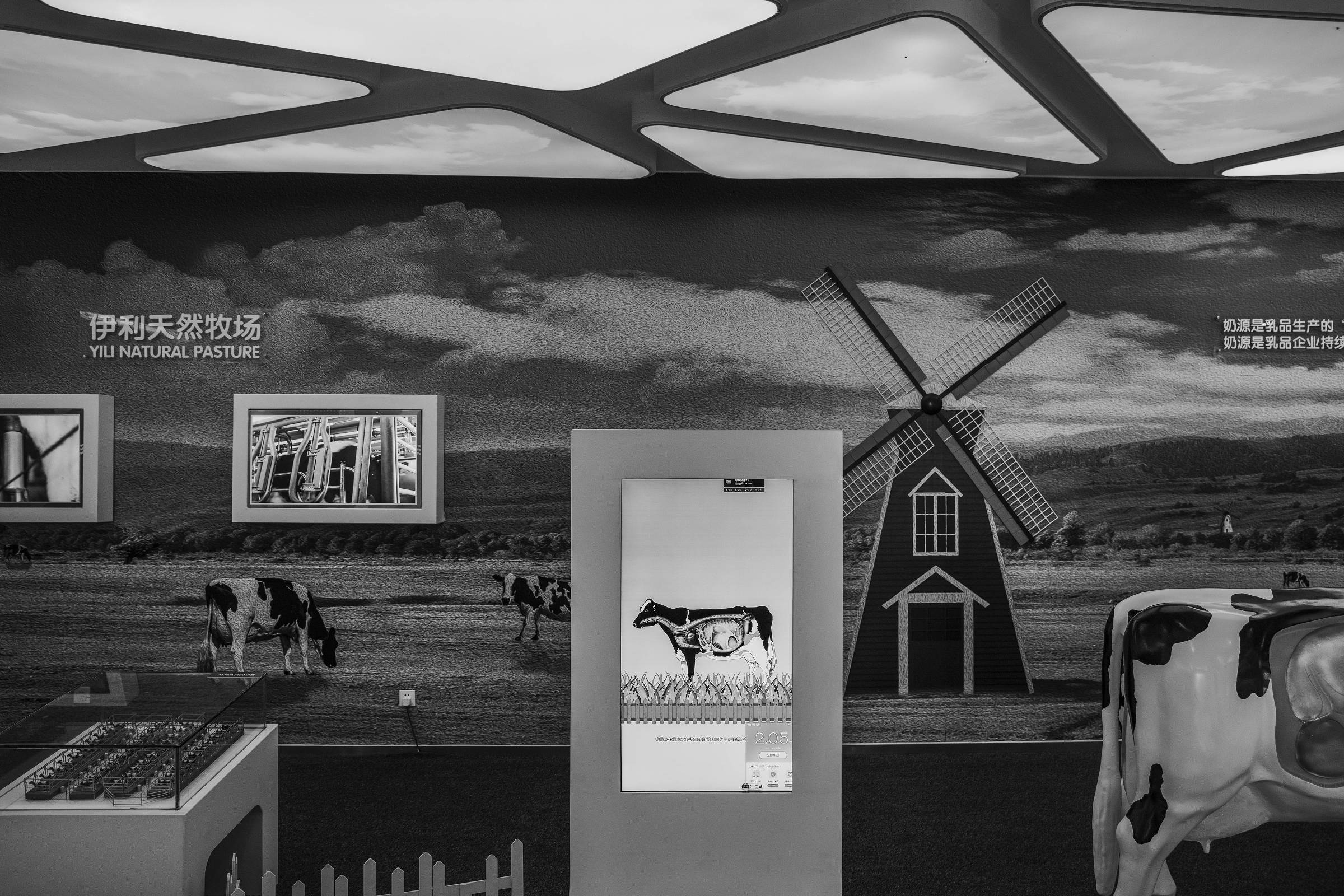

State-subsidized Chinese cattle farmer tries to tie a cow in a rural area of China; "high-tech" installations in one of the largest milk factories in the world, in China

Actions like these and formidable Chinese growth in the last few decades are why China has had the most significant success in the world with poverty reduction.

According to the Global Inequality Report of the Paris School of Economics, where the economist Thomas Piketty works, since the beginning of the Deng Xiaoping reforms in 1978, China's median income has jumped 800% compared to a US high of 63 % and in France, 38%.

However, like almost every country in the world, increased inequality accompanied China's poverty reduction. The wealthiest 10% and the poorest 50% at one point each took home 25 percent of the nation's income.

Today, the wealthiest 10% earn 40% of China's national income; and the poorest 50%, less than 15%.

As was the case of China, many countries that have successfully fought extreme poverty or have experienced rapid growth have also seen increased inequality, due to the greater gains made by the sectors driving development, whose participants have benefited proportionally more.

In China, the increased income accumulated since 1980 by the wealthies 10 per cent comes to 1,230 per cent; in the case of the 50 per cent poorest, the number is 386 per cent. Income concentration in China coincided with the wave of privatizations between 1998 and 2006.

In that period, the middle class (the middle 40% "middle" among the wealthiest 10% the poorest 50%) gained 700%, just slightly below the overall average.

T he good news in the Chinese story is that inequality, although extremely high, has had limited growth for almost 15 years.

It's due to China and its Asian neighbors that Earth today can be called a "middle-class planet."

More than half the population (about 3.8 billion people) live between US$ 11 and US$ 110 per day and has enough income to buy refrigerators or motorcycles, according to the Brookings Institution of Washington.

"Even where inequality is still increasing, growth in countries such as China, India, Vietnam, the Philippines or Indonesia is very strong, to the point of offsetting the rise in income disparity and causing the expansion of its middle classes," said Homi Kharas, Deputy Director for the Global Economy and Development program at the Brookings Institution.

In China, both the average income of the poorest 50% (equivalent to R$ 1,500 monthly) and that of the middle class (R$ 5,400) has already surpassed, by a small margin, that of Brazil, according to the criteria of the Global Inequality Report.

However, the average earnings of the wealthiest 10% (R$ 20,400 monthly) remain below the level of Brazil (R$ 28,750) in this group.

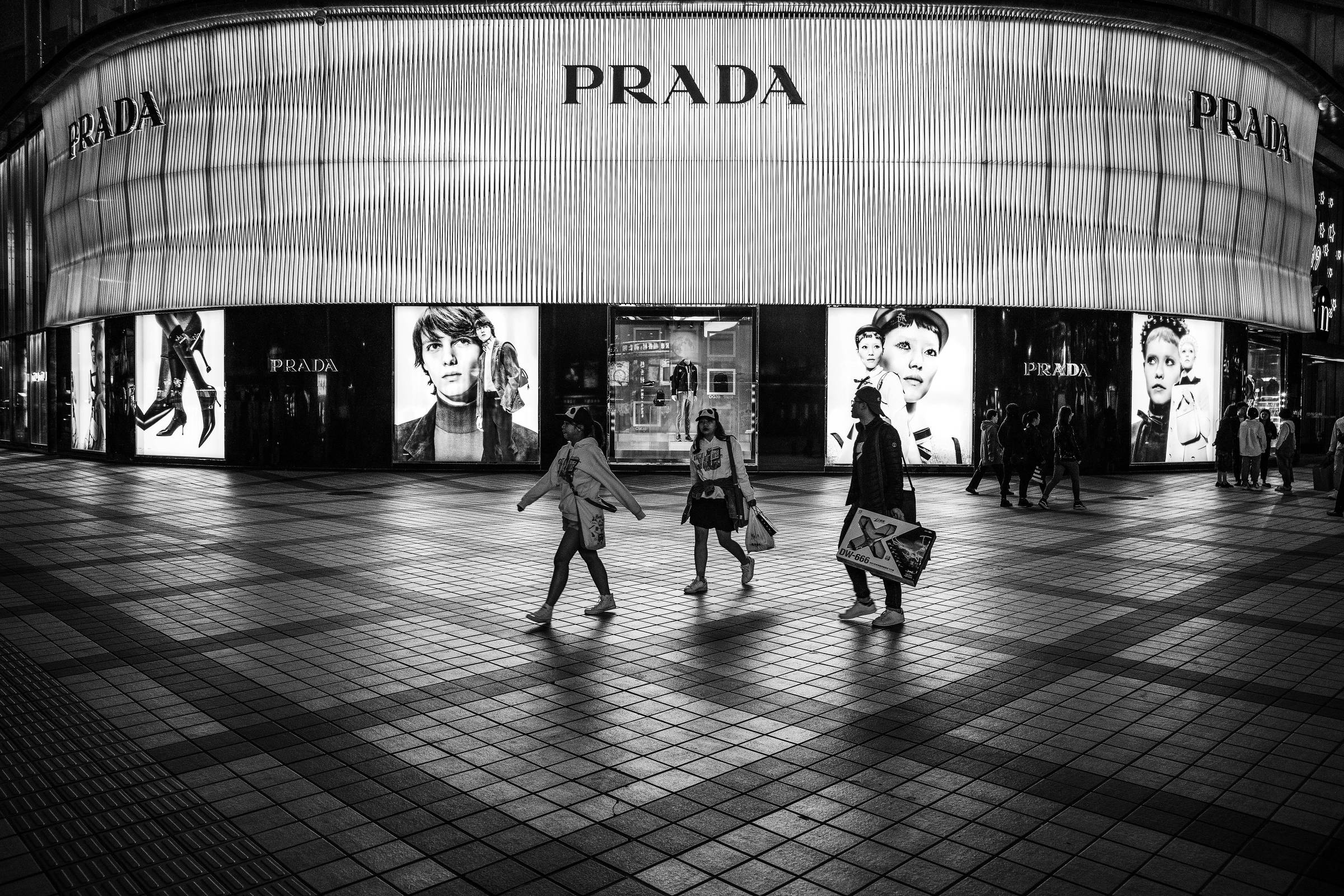

Women in traditional Chinese clothes in front of the entrance to the Forbidden City; it is common for groups of people to gather to dance in the morning or at the end of the day in downtown Beijing

According to Lucas Chancel, coordinator of the report, China and other Asians promote "the happy side of globalization," which has led to improved incomes in these highly populated and export-oriented countries.

"The other side of globalization is that income grows at a meager pace for the working classes in North America and certain European countries. Some politicians realize this, and we see the effects," said Chancel, referring to the waves of populism and protectionism of recent years.

Although China's "state capitalism" model is criticized heavily by Western leaders, especially Donald Trump in the US, some inequality experts agree that it works in terms of fighting poverty.

"In China, private companies produce about 70 percent of all value-added and employ almost 80 percent of the workforce, which is salaried. So there are legally free people working," said Branko Milanovic, author of "Global Inequality" (Harvard University Press).

"That does not mean that the Chinese state does not play an active role. However, it is not very different from what the French state did in the 1980s."

Security orientates the public at The Forbidden City in Beijing; at the entrance to the palace, photo of leader Mao Tsé-Tung

Over the past few decades, Chinese growth emerged out of infrastructure investments and loans to state-owned enterprises for export platforms that used intensive and cheap labor.

China's investment rate is nearly half of its GDP and is now more than double the average for rich countries. Household consumption accounts for one-third of GDP, half of the rate in developed countries.

With the increase in the average income, experts expected the following: that public investments would reignite, the state would sell a large part of its 150 thousand state-owned companies, and that consumption would become the main engine of growth.

Although shopping malls full of people dot China's large Chinese cities, the arrival of Xi Jinping to power has led to an expansion of the state's share of the economy.

From 2013, for example, state-owned banks increased their share of bank loans from 35 percent to more than 80 percent, according to economist Nicholas Lardy of the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

The new interventionism is attempting to accelerate investment again the smallest in 20 years and the economy.

With a growth of about 10% per year until the 2008 global crisis, the Chinese GDP is losing strength and this year should grow between 6.5% and 6% or even less depending on the impact of the trade war with the United States.

The risk of this strategy, according to experts, would be to over-anabolic the economy with state loans for businesses that do not meet corresponding demand in the future.

The journalists traveled to China at the invitation of the National Association of Journalists

Company meeting room in China; more and more companies are opening up Chinese Communist Party cells